Warner cartoon no. 333.

Release date: July 5, 1941.

Series: Merrie Melodies.

Supervision: Tex Avery.

Producer: Leon Schlesinger.

Starring: Mel Blanc (Bugs Bunny), Kent Rogers (Willoughby) (?).

Story: Michael Maltese.

Animation: Bob McKimson.

Musical Direction: Carl W. Stalling.

Sound: Treg Brown (uncredited).

Synopsis: A dim-witted dog is on the look out for a rabbit. Being a threat to Bugs, he takes advantage of the dog's lack of intelligence with his smart tactics.

Throughout most of the early Bugs Bunny shorts, (with the exceptions of Tortoise Beats Hare or Elmer's Pet Rabbit), the Warner directors were still writing the same story formula for Bugs Bunny, involving Bugs outwitting several different characters each short.

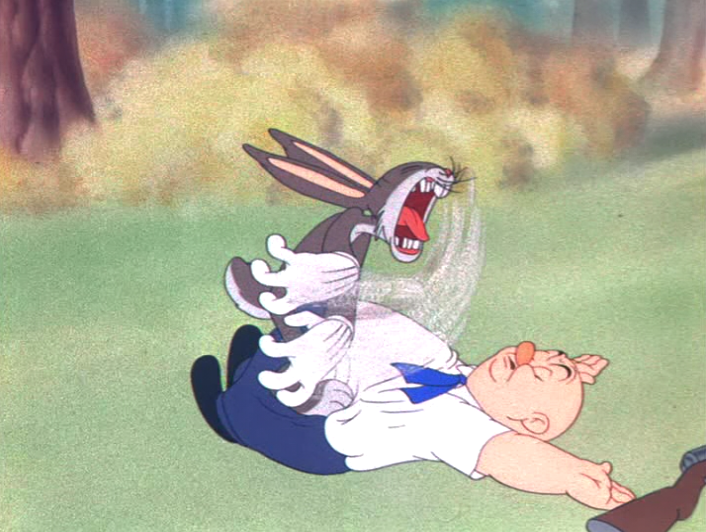

![]() With that said, being a very common trait of Bugs Bunny throughout his career, later shorts on the other hand had more focus towards story and each short had different dilemmas. In this short, this is really the basic, A Wild Hare-type story.

With that said, being a very common trait of Bugs Bunny throughout his career, later shorts on the other hand had more focus towards story and each short had different dilemmas. In this short, this is really the basic, A Wild Hare-type story.

Instead of a hunter: Bugs is being pursued by a dim-witted dog (if you wish to call him Willoughby, fine). Since this is a short where the story formula was still largely the same, Tex still had a new set of gags to invent, and this short he is certainly experimenting with new gag ideas, that would still seem beyond what animated cartoons, then, offered.

The short starts off like how an earlier Bugs Bunny short might begin, the antagonist of the short appears first, as the purpose is the audience would be wanting to know the antagonist better.

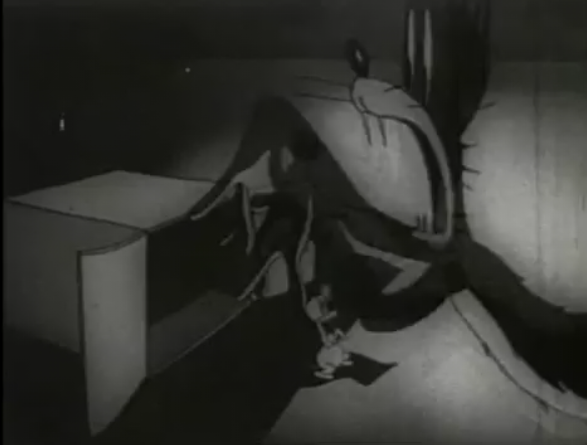

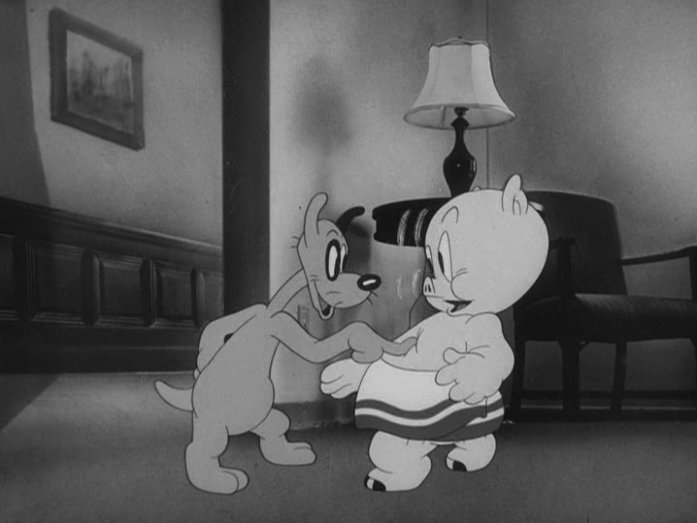

![]() Willoughby is seen sniffing out for the scent of a rabbit in the forest. He introduces himself, and explains to the audience of his intended target.

Willoughby is seen sniffing out for the scent of a rabbit in the forest. He introduces himself, and explains to the audience of his intended target.

![]() Note the walk-cycle that Tex gives to Willoughby, which shows how Tex's walk cycles only get even more bizarre in each short he is making. With the walk animated by Bob McKimson, Tex shows an urge of attempting to create funnier animation, which is becoming more noticeable in this short.

Note the walk-cycle that Tex gives to Willoughby, which shows how Tex's walk cycles only get even more bizarre in each short he is making. With the walk animated by Bob McKimson, Tex shows an urge of attempting to create funnier animation, which is becoming more noticeable in this short.

![]() This then follows with a glimpse of Bugs Bunny's ears once Willoughby discovers a rabbit hole. Bugs' ears then appear out of scene. This requires stronger character animation, as well as a heavier set-up from a scene used several times previously.

This then follows with a glimpse of Bugs Bunny's ears once Willoughby discovers a rabbit hole. Bugs' ears then appear out of scene. This requires stronger character animation, as well as a heavier set-up from a scene used several times previously.

Instead of Elmer's gun, Willoughby's mouth is held wide open, and the detail on the teeth emphasise on the viciousness the dog could be. And so, Bugs outwits Willoughby with his presence, where Willoughby is too late for his double-take delivery, a gag formula that Tex loved to use between two parallel characters. Once Willoughby realises his error, this follows through a sophisticated, walk-cycle of Bugs Bunny who walks in rhythm to Carl Stalling and Milt Franklyn's synchronisation to I Was Strolling Through the Park One Day. The walk-cycle, likely animated by McKimson or Virgil Ross, shows how the animators at Warners were becoming more confident in exploring their animation, and that cycle alone expresses not only how much better the animators got, but also the freedom to explore several aspects when animating.

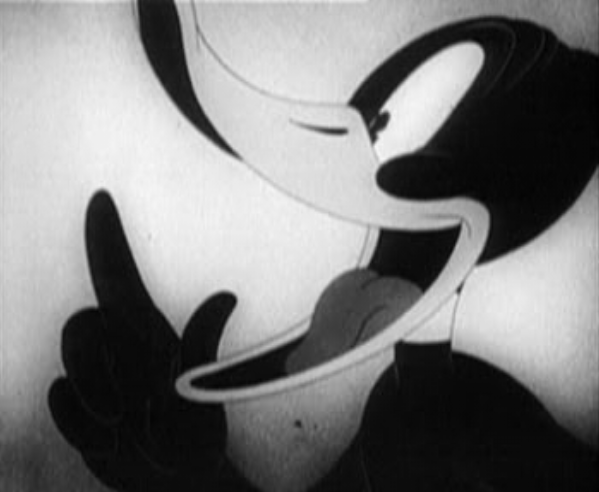

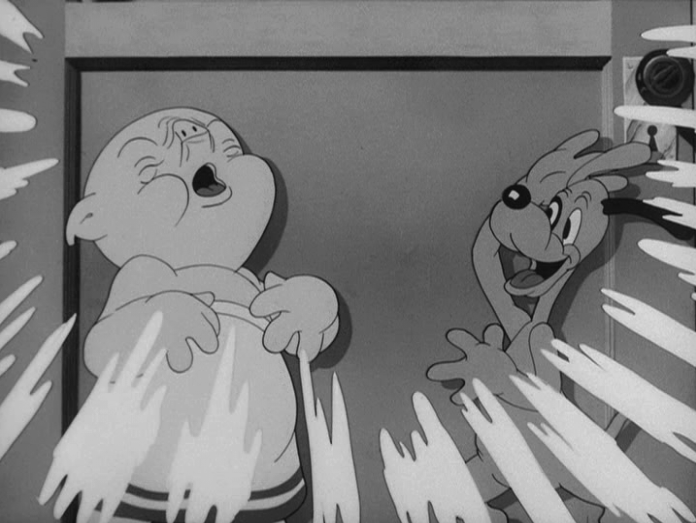

A great example of how Tex Avery was definitely allowing his animators to explore further in what they could do with animation happens in the following sequence. This classic sequence in the short centres on Bugs mimicking Willoughby's facial expressions in a psychological effect to have the dog's mind focused on making consistent facial expressions.

![]()

The sequence, animated by Rod Scribner, is great for what Tex was wanting his animators to do, as well as what he was attempting to explore. The wacky Tex Avery everybody would come to associate with is only at the tip of the iceberg in this short, and Scribner nails on how Tex probably visioned the scene.

![]() Bugs and the dog go through some far-out expressions, such as the details of their mouths and Scribner was exploring the broadness of his animation in a lot of bizarre ways which no animator in Tex's unit did, he tries to top each pose with a more exaggerated feel towards it. Tex's comic timing is also a striking example of how he is attempting to achieve funnier timing.

Bugs and the dog go through some far-out expressions, such as the details of their mouths and Scribner was exploring the broadness of his animation in a lot of bizarre ways which no animator in Tex's unit did, he tries to top each pose with a more exaggerated feel towards it. Tex's comic timing is also a striking example of how he is attempting to achieve funnier timing.

The dog, making consistent face-making is already been fooled, to the point where Bugs is no longer a threat to the dog. It builds up with a typical Tex Avery delivery, as he holds a sign reading "Silly, isn't he?", but only returns from his hole with a giant baseball bat. Tex's use of colour to follow the effects is only seen at a brief glimpse, to find that the scene quickly follows with Bugs holding onto a damaged baseball bat. Tex's time couldn't get better for the build up that it got to. He is already succeeding in achieving funnier timing, and his talent of it is already glowing in this sequence. Stalling's choice for Mendelssohn's Spring Song heard briefly in the underscore is an excellent little cliche to emphasise of Bugs's innocent posture.

![]() The following sequence, a gag which is largely borrowed from Tex's The Crackpot Quail, is once again another challenge in terms of animation in order to make the gag easier to follow as well as visualised in a comical way. Bugs, deciding to dive underwater, and placing his bathing cap, dives underwater, but only to end up being pursued by Willoughby on the way.

The following sequence, a gag which is largely borrowed from Tex's The Crackpot Quail, is once again another challenge in terms of animation in order to make the gag easier to follow as well as visualised in a comical way. Bugs, deciding to dive underwater, and placing his bathing cap, dives underwater, but only to end up being pursued by Willoughby on the way.

![]()

The effects animation (did they have other effects animators at that time, other than Ace Gamer?), is well achieved in order for the two characters to be communicated under water. One of the highlights would be through the communication of bubbles rising from the surface.

![]() We can identify Bugs from underwater due to the frantic speed he is travelling through underwater, but once he's stopped by Willoughby, the silence then deepens. Their identities are somewhat more obvious as Bugs' ears and Willoughby's tail rise from the surface.

We can identify Bugs from underwater due to the frantic speed he is travelling through underwater, but once he's stopped by Willoughby, the silence then deepens. Their identities are somewhat more obvious as Bugs' ears and Willoughby's tail rise from the surface.

Tex only gets even more bizarre with the gag when a giant log is seen in the middle of a lake. Bugs travels straight towards the log, but manages to dodge by having both ears separate to each corner. Tex used a slightly, though more subtle gag in The Crackpot Quail which featured Willoughby sniffing the quail's gap, and at one point the tracks then become greatly separated. Here, it is more bizarrely visualised, as the ears separating is somewhat very surreal compared to the previous short.

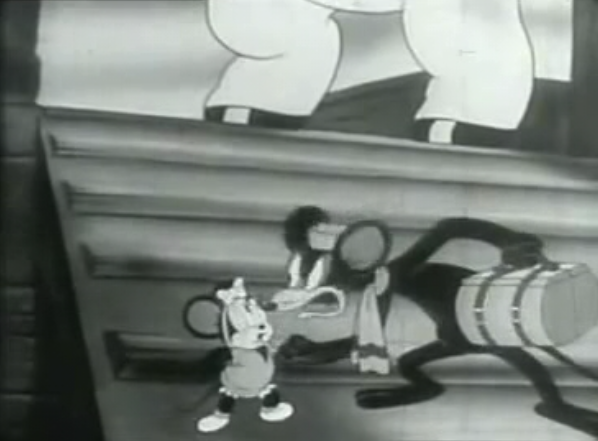

The following sequence is another animated challenge, though it requires a lot of strong character animation, and methodical skills. The gag, being rather straightforward from Mike Maltese's writing: shows Bugs standing on top of Willoughby who is still hunting for Bugs, though without noticing his presence above him. Bugs, pacing up and down Willoughby, comes up with another strategy, and thus tickles him, causing Willoughby to scratch.

Whilst the gag delivery is somewhat basic in terms of how it looks how, the technical side would be a lot more challenging. For one, Willoughby would have to be animated separately, especially since Willoughby, for a small part of the sequence is animated as a walk cycle. Bugs, however, is animated separately, and thus making staging difficult for the animator, in order to achieve an accurate line position for the dog's back. It's likely that both animators were animated at the same time, once Bugs begins to tickle Willoughby, considering how the action is done.

The following sequence, and despite some great strategies and sequences invented by Mike Maltese: the following sequence is somewhat cliched. Willoughby, suspecting the rabbit is inside the bark of a tree has his hand reaching out on the other end of the tree. Bugs, once again taking advantage of the dim-witted dog, grabs out a tomato to place on Willoughby's hand.

![]()

Once Willoughby squeezes the tomato in his hand, Willoughby mistakes the tomato juice as Bugs' blood, crying, "I crushed him". He continues to cry, and expressing pity towards himself for killing the rabbit.

I've never been a personal fan of these sequences, and despite making the characters just appear even more foolish: it never made sense to me of their sudden sadness for killing an animal they intended to kill. Perhaps the impact of killing had reflected poorly on them? Well, a cartoon's a cartoon. Willoughby, mourning the "loss" of Bugs, arrives at his rabbit hole to place flowers besides it. Still sobbing, Bugs approaches on top of his hole and feeling flattered, puckers up to Willoughby: "For me, doc? Oh you darling".

This then leads to the cartoon's climax, and without doubt, the most memorable sequence in the short for several factors. One factor was that the sequence was reportedly considered to be the longest fall in cinematic history.

![]() Tex Avery, who was taking new levels that Leon Schlesinger considered dangerous, had wanted to test the audience's patience by having the characters not fall for a great distance, but a total of three falls, which was cut from the print that everybody knows of today.

Tex Avery, who was taking new levels that Leon Schlesinger considered dangerous, had wanted to test the audience's patience by having the characters not fall for a great distance, but a total of three falls, which was cut from the print that everybody knows of today.

![]() For further information on the removed sequence, read Thad K.'s enlightening blog post. Though the sequence was considered to be the reason why Tex Avery quit the studios (which wasn't the factor); it just goes to show how Tex was already becoming far more ambitious with his cartoon directing, but his original ending just happened to flop.

For further information on the removed sequence, read Thad K.'s enlightening blog post. Though the sequence was considered to be the reason why Tex Avery quit the studios (which wasn't the factor); it just goes to show how Tex was already becoming far more ambitious with his cartoon directing, but his original ending just happened to flop.

Despite the original ending, the edited version does feel somewhat a lot more better in terms of the short's cliffhanger. The audience feel for Bugs Bunny, their favourite character, and this was Tex's vision of testing the audience's mind on how they could make it alive. The problem is solved with them skidding to the grounds safely, with Bugs remarking to the audience, "Ehh, fooled ya didn't he", in which Willoughby responds, "Uh, yeah". The delivery works well as an ending. Whilst the original ending would have shown Tex exaggerating the significant amount of feet they are falling and landing from, it does feel somewhat very anti-climatic, and shows how Tex's original approach didn't work out.

In all, for a short that did itself have a repeated story formula: this allowed Tex to explore at different heights in terms of approach to gags, as well as timing. Tex's timing is only getting faster and edgier compared to his previous shorts, and his idea for gag build-up has certainly gone to high levels which he hadn't yet achieved before. Of course, there are many sequences in the short where Tex had recycled certain gags, though the mimic sequence as well as the fall stand out as being far more original not only as to how they were timed, but also how they were delivered. Mike Maltese, appears to be under much of Tex's influence in the short as many of the sequences feel very Tex Avery oriented, and little of the charms from Mike Maltese. In all, it was an entertaining short for a Bugs Bunny cartoon, a character who is only getting funnier and broader in each short. The shorts by this point are only becoming a tad faster and edgier, and thus giving Warners a reputable name.

Rating: 3.5/5.

Release date: July 5, 1941.

Series: Merrie Melodies.

Supervision: Tex Avery.

Producer: Leon Schlesinger.

Starring: Mel Blanc (Bugs Bunny), Kent Rogers (Willoughby) (?).

Story: Michael Maltese.

Animation: Bob McKimson.

Musical Direction: Carl W. Stalling.

Sound: Treg Brown (uncredited).

Synopsis: A dim-witted dog is on the look out for a rabbit. Being a threat to Bugs, he takes advantage of the dog's lack of intelligence with his smart tactics.

Throughout most of the early Bugs Bunny shorts, (with the exceptions of Tortoise Beats Hare or Elmer's Pet Rabbit), the Warner directors were still writing the same story formula for Bugs Bunny, involving Bugs outwitting several different characters each short.

With that said, being a very common trait of Bugs Bunny throughout his career, later shorts on the other hand had more focus towards story and each short had different dilemmas. In this short, this is really the basic, A Wild Hare-type story.

With that said, being a very common trait of Bugs Bunny throughout his career, later shorts on the other hand had more focus towards story and each short had different dilemmas. In this short, this is really the basic, A Wild Hare-type story.Instead of a hunter: Bugs is being pursued by a dim-witted dog (if you wish to call him Willoughby, fine). Since this is a short where the story formula was still largely the same, Tex still had a new set of gags to invent, and this short he is certainly experimenting with new gag ideas, that would still seem beyond what animated cartoons, then, offered.

The short starts off like how an earlier Bugs Bunny short might begin, the antagonist of the short appears first, as the purpose is the audience would be wanting to know the antagonist better.

Willoughby is seen sniffing out for the scent of a rabbit in the forest. He introduces himself, and explains to the audience of his intended target.

Willoughby is seen sniffing out for the scent of a rabbit in the forest. He introduces himself, and explains to the audience of his intended target. Note the walk-cycle that Tex gives to Willoughby, which shows how Tex's walk cycles only get even more bizarre in each short he is making. With the walk animated by Bob McKimson, Tex shows an urge of attempting to create funnier animation, which is becoming more noticeable in this short.

Note the walk-cycle that Tex gives to Willoughby, which shows how Tex's walk cycles only get even more bizarre in each short he is making. With the walk animated by Bob McKimson, Tex shows an urge of attempting to create funnier animation, which is becoming more noticeable in this short. This then follows with a glimpse of Bugs Bunny's ears once Willoughby discovers a rabbit hole. Bugs' ears then appear out of scene. This requires stronger character animation, as well as a heavier set-up from a scene used several times previously.

This then follows with a glimpse of Bugs Bunny's ears once Willoughby discovers a rabbit hole. Bugs' ears then appear out of scene. This requires stronger character animation, as well as a heavier set-up from a scene used several times previously.Instead of Elmer's gun, Willoughby's mouth is held wide open, and the detail on the teeth emphasise on the viciousness the dog could be. And so, Bugs outwits Willoughby with his presence, where Willoughby is too late for his double-take delivery, a gag formula that Tex loved to use between two parallel characters. Once Willoughby realises his error, this follows through a sophisticated, walk-cycle of Bugs Bunny who walks in rhythm to Carl Stalling and Milt Franklyn's synchronisation to I Was Strolling Through the Park One Day. The walk-cycle, likely animated by McKimson or Virgil Ross, shows how the animators at Warners were becoming more confident in exploring their animation, and that cycle alone expresses not only how much better the animators got, but also the freedom to explore several aspects when animating.

A great example of how Tex Avery was definitely allowing his animators to explore further in what they could do with animation happens in the following sequence. This classic sequence in the short centres on Bugs mimicking Willoughby's facial expressions in a psychological effect to have the dog's mind focused on making consistent facial expressions.

The sequence, animated by Rod Scribner, is great for what Tex was wanting his animators to do, as well as what he was attempting to explore. The wacky Tex Avery everybody would come to associate with is only at the tip of the iceberg in this short, and Scribner nails on how Tex probably visioned the scene.

Bugs and the dog go through some far-out expressions, such as the details of their mouths and Scribner was exploring the broadness of his animation in a lot of bizarre ways which no animator in Tex's unit did, he tries to top each pose with a more exaggerated feel towards it. Tex's comic timing is also a striking example of how he is attempting to achieve funnier timing.

Bugs and the dog go through some far-out expressions, such as the details of their mouths and Scribner was exploring the broadness of his animation in a lot of bizarre ways which no animator in Tex's unit did, he tries to top each pose with a more exaggerated feel towards it. Tex's comic timing is also a striking example of how he is attempting to achieve funnier timing.The dog, making consistent face-making is already been fooled, to the point where Bugs is no longer a threat to the dog. It builds up with a typical Tex Avery delivery, as he holds a sign reading "Silly, isn't he?", but only returns from his hole with a giant baseball bat. Tex's use of colour to follow the effects is only seen at a brief glimpse, to find that the scene quickly follows with Bugs holding onto a damaged baseball bat. Tex's time couldn't get better for the build up that it got to. He is already succeeding in achieving funnier timing, and his talent of it is already glowing in this sequence. Stalling's choice for Mendelssohn's Spring Song heard briefly in the underscore is an excellent little cliche to emphasise of Bugs's innocent posture.

The following sequence, a gag which is largely borrowed from Tex's The Crackpot Quail, is once again another challenge in terms of animation in order to make the gag easier to follow as well as visualised in a comical way. Bugs, deciding to dive underwater, and placing his bathing cap, dives underwater, but only to end up being pursued by Willoughby on the way.

The following sequence, a gag which is largely borrowed from Tex's The Crackpot Quail, is once again another challenge in terms of animation in order to make the gag easier to follow as well as visualised in a comical way. Bugs, deciding to dive underwater, and placing his bathing cap, dives underwater, but only to end up being pursued by Willoughby on the way.

The effects animation (did they have other effects animators at that time, other than Ace Gamer?), is well achieved in order for the two characters to be communicated under water. One of the highlights would be through the communication of bubbles rising from the surface.

We can identify Bugs from underwater due to the frantic speed he is travelling through underwater, but once he's stopped by Willoughby, the silence then deepens. Their identities are somewhat more obvious as Bugs' ears and Willoughby's tail rise from the surface.

We can identify Bugs from underwater due to the frantic speed he is travelling through underwater, but once he's stopped by Willoughby, the silence then deepens. Their identities are somewhat more obvious as Bugs' ears and Willoughby's tail rise from the surface.Tex only gets even more bizarre with the gag when a giant log is seen in the middle of a lake. Bugs travels straight towards the log, but manages to dodge by having both ears separate to each corner. Tex used a slightly, though more subtle gag in The Crackpot Quail which featured Willoughby sniffing the quail's gap, and at one point the tracks then become greatly separated. Here, it is more bizarrely visualised, as the ears separating is somewhat very surreal compared to the previous short.

The following sequence is another animated challenge, though it requires a lot of strong character animation, and methodical skills. The gag, being rather straightforward from Mike Maltese's writing: shows Bugs standing on top of Willoughby who is still hunting for Bugs, though without noticing his presence above him. Bugs, pacing up and down Willoughby, comes up with another strategy, and thus tickles him, causing Willoughby to scratch.

Whilst the gag delivery is somewhat basic in terms of how it looks how, the technical side would be a lot more challenging. For one, Willoughby would have to be animated separately, especially since Willoughby, for a small part of the sequence is animated as a walk cycle. Bugs, however, is animated separately, and thus making staging difficult for the animator, in order to achieve an accurate line position for the dog's back. It's likely that both animators were animated at the same time, once Bugs begins to tickle Willoughby, considering how the action is done.

The following sequence, and despite some great strategies and sequences invented by Mike Maltese: the following sequence is somewhat cliched. Willoughby, suspecting the rabbit is inside the bark of a tree has his hand reaching out on the other end of the tree. Bugs, once again taking advantage of the dim-witted dog, grabs out a tomato to place on Willoughby's hand.

Once Willoughby squeezes the tomato in his hand, Willoughby mistakes the tomato juice as Bugs' blood, crying, "I crushed him". He continues to cry, and expressing pity towards himself for killing the rabbit.

I've never been a personal fan of these sequences, and despite making the characters just appear even more foolish: it never made sense to me of their sudden sadness for killing an animal they intended to kill. Perhaps the impact of killing had reflected poorly on them? Well, a cartoon's a cartoon. Willoughby, mourning the "loss" of Bugs, arrives at his rabbit hole to place flowers besides it. Still sobbing, Bugs approaches on top of his hole and feeling flattered, puckers up to Willoughby: "For me, doc? Oh you darling".

This then leads to the cartoon's climax, and without doubt, the most memorable sequence in the short for several factors. One factor was that the sequence was reportedly considered to be the longest fall in cinematic history.

Tex Avery, who was taking new levels that Leon Schlesinger considered dangerous, had wanted to test the audience's patience by having the characters not fall for a great distance, but a total of three falls, which was cut from the print that everybody knows of today.

Tex Avery, who was taking new levels that Leon Schlesinger considered dangerous, had wanted to test the audience's patience by having the characters not fall for a great distance, but a total of three falls, which was cut from the print that everybody knows of today. For further information on the removed sequence, read Thad K.'s enlightening blog post. Though the sequence was considered to be the reason why Tex Avery quit the studios (which wasn't the factor); it just goes to show how Tex was already becoming far more ambitious with his cartoon directing, but his original ending just happened to flop.

For further information on the removed sequence, read Thad K.'s enlightening blog post. Though the sequence was considered to be the reason why Tex Avery quit the studios (which wasn't the factor); it just goes to show how Tex was already becoming far more ambitious with his cartoon directing, but his original ending just happened to flop.Despite the original ending, the edited version does feel somewhat a lot more better in terms of the short's cliffhanger. The audience feel for Bugs Bunny, their favourite character, and this was Tex's vision of testing the audience's mind on how they could make it alive. The problem is solved with them skidding to the grounds safely, with Bugs remarking to the audience, "Ehh, fooled ya didn't he", in which Willoughby responds, "Uh, yeah". The delivery works well as an ending. Whilst the original ending would have shown Tex exaggerating the significant amount of feet they are falling and landing from, it does feel somewhat very anti-climatic, and shows how Tex's original approach didn't work out.

In all, for a short that did itself have a repeated story formula: this allowed Tex to explore at different heights in terms of approach to gags, as well as timing. Tex's timing is only getting faster and edgier compared to his previous shorts, and his idea for gag build-up has certainly gone to high levels which he hadn't yet achieved before. Of course, there are many sequences in the short where Tex had recycled certain gags, though the mimic sequence as well as the fall stand out as being far more original not only as to how they were timed, but also how they were delivered. Mike Maltese, appears to be under much of Tex's influence in the short as many of the sequences feel very Tex Avery oriented, and little of the charms from Mike Maltese. In all, it was an entertaining short for a Bugs Bunny cartoon, a character who is only getting funnier and broader in each short. The shorts by this point are only becoming a tad faster and edgier, and thus giving Warners a reputable name.

Rating: 3.5/5.